SEWAGE

IS

ART!

HEALING OF PLACE WITH "CHI"

TOM BENDER

September 1995

Conventional architecture today seeks primarily

visual excitement and impact, but rarely creates places that nurture our

bodies, minds, and spirits. This study demonstrates an alternative approach

to the making of place - creating meaningful and nurturing places through

design incorporating modern application of feng-shui or geomancy.

Rather than the conventional owner's demands of "I want..., I want...",

it begins with the question, "What is the most we can give

to users of the place, to its surroundings and community, to the future,

and to all of life?" It suggests that a giving-centered design

process can create places which more successfully contribute to the true

goals of their creators and users than conventional and even "green"

design. It recognizes that embodiment of positive and nurturing values can

generate the greatest power of a place to affect us, to heal and enhance

our lives and community.

Feng-shui (literally 'wind and water') is the Chinese name for their

traditional approach to design of cities, homes, temples and tombs to align

our actions harmoniously with the universe. It is a multi-dimensional collection

of practices, principles, sciences and art - including what we would today

call geophysics, ecology, psychology, spiritual practice, symbolism, chi

(energy of life), astrology, and just good common sense. Feng-shui

has shown that there are demonstrable geophysical energies in the earth

which are modified by topographical features, and which influence our lives.

It has shown also that our own vital life energy - embodying our love, fear,

anger, or joy - impacts and alters the energy of the places we inhabit,

and consequently affects others that use those places.

Traditional practice of "feng-shui" or geomancy often constituted

a highly competitive search to obtain and flaunt the most geomantically

favorable site or design, to give comparative advantage to one's life or

success. Such sites had the most dominant views and positions, favorable

breezes, exposures, terrain, neighbors, etc. In contrast, modern feng-shui

practice often recognizes what is soon learned in a family relationship

- that the happiness and well-being of each is dependent upon the health

and well-being of all. It seeks improvement of the qualities of physical

surroundings which can benefit an entire community, recognizing that the

position of generator of that good brings the greatest benefits of all.

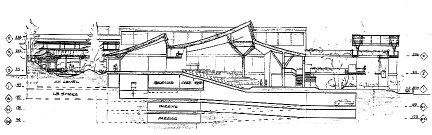

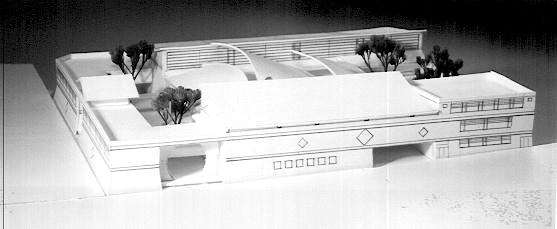

In this case, choice of site was not possible. The study was an entry in

a competition for design of a new Museum of Korean Art and Culture to be

built in Los Angeles, CA. The site was already determined, and its context

and qualities were not encouraging. It was located in a commercial ghetto

in a smog-ridden and automobile-dominated urban area of Los Angeles, filled

with racial and class tensions and the aftermath of rioting and arson. The

site was rubble-strewn and barren, with virtually no trace of the natural

ecological community remaining. The site starkly reflected the results of

a society based on greed, on self-centeredness and materialism, on taking

rather than giving. This provided an appropriate challenge to find what

could be given to a place and its community to nurture and improve its energy

and life, and to tackle head-on the issue of healing and revitalizing the

places most damaged by our actions.

Our energy connections with a place occur through

our bodies, our minds, and our hearts. If its neighborhood is too scary

to enter, noone will visit a museum, no matter how beautiful we make it.

If our surroundings reflect back to us only the values of greed, lack of

caring, and failure, we are unlikely to become caring, giving, successful

people. But if we initiate caring for a place, for its people, and honoring

a belief in a good future, it will come to reflect those values, too, and

become a support for the people who live within it. The most important change

any building on this site could demonstrate is a change in the values it

embodies and establishment of the precept of 'giving' rather than 'taking'

as a basis for interaction.

One basic strategy chosen was to take what is considered waste, and turn

it into wealth which can enrich the community. We chose probably the least

likely action possible - of taking the community sewer and rerouting it

onto the site. The sewage of the neighborhood would be pumped onto the roof

of the museum, given advanced biological treatment, and its nutrients used

to support rooftop produce gardens to provide fresh produce to the neighborhood.

The produce would be sold at a green grocer incorporated into the public

areas of the site, which would provide incentive and opportunity for everyone

in the neighborhood to drop in, linger, and relax, as well as obtain fresh,

healthy produce.

The wastewater from the produce gardens would then be distributed along

the surrounding streets to irrigate street tree plantings of native California

live oaks. This would help restore greenery, shade, and some of the native

ecology back into the area, as well as decreasing temperature swings. It

would also provide groundwater aquifer recharge, while demonstrating that

a community can take action to improve itself.

This may seem at first to be far removed from the mission of an art museum

and culture center. It is a capability for "giving", however,

which is inherent in any facility in a neighborhood with community consciousness

and a large roof area. It also has a particular appropriateness in KOMA's

case. KOMA does not have a traditional museum's goal of just storing old

objects. Its goal is to honor its particular cultural heritage, transmit

its skills and values, heal tensions in the community, and stimulate a positive

new modern synthesis of culture. For that primary role of the center to

even begin to succeed, however, it has to show leadership, to become a welcome

and valued part of the community and to draw people into and contributing

to its activities. Vitality is a goal of art, and any tool which helps achieve

that vitality creates an appropriate art form. The resultant roof gardens,

street landscaping, and facility gardens are a true form of art as well

as wealth - created out of the once worthless waste of community sewage.

In this context, sewage truly is art, and the neighborhood an appropriate

canvas!

A vision put into action, of a community enriching and empowering itself

through discovering its least likely source of wealth, can be an essential

element of survival, leadership, and of synthesizing a new and vibrant culture

in this time and place. It also provides several potential concrete benefits

- recapture and savings of sewage treatment and disposal costs, avoiding

use of chemical fertilizers, keeping nutrients and food production in the

neighborhood and in control of the residents, and providing an attraction

to bring more than just Korean neighborhood residents into the project.

It turns unused roof areas that conventionally contribute only to climate

extremes into green and productive areas. It provides areas of economic

value on the project property beyond those otherwise limited by city zoning

codes. Perhaps most importantly, it demonstrates a commitment to improving

the quality of the community, and concern for the health and well-being

of all members of the community - human and otherwise.

This first level of 'chi' design changed the energy of the neighborhood

- replacing values that destroy, pave over, ignore, and take, and setting

in motion ones that support and restore life, diversity, caring, and giving.

Feng-shui acknowledges the importance of our continuing awareness

of our dependence upon and place in the web of life - both as a matter of

survival and as a source of joy and happiness. The aptness of the natural

community of life that evolves out of long interaction in a place is a visceral

demonstration of 'fit-ness', and actions taken to initiate its restoration

and our proper fit into it some of the most important actions we can take

with a place, apart from the practical benefits of such actions.

A second level of 'chi' design for KOMA changed the ecology of the site

itself. It constituted actions around and within the site itself to

improve the microclimate and ecological aspects of the facility. In addition

to the rooftop produce garden, four other separate garden or green elements

were designed into the project - a powerful traditional Korean garden in

the heart of the site, a community-use "forecourt" garden area;

an outside neighborhood "pocket garden" along the sidewalk adjacent

to the west entrance to the project, and the native street tree plantings

surrounding the site. These quieted the site, freshened the air, exchanged

carbon dioxide for oxygen, provided places for birds, insects, plants, and

reestablished a natural ecological community on the site.

Other water features were part of the design - a gurgling and splashing

"moat" surrounding the building, the waterfall and pond in the

pocket garden, fountains at the building corner and at the "spirit

wall" at the south entrance, and fountains and water features at the

entrances. They were used to increase anions in the air to counter the "Santa

Anna" winds, cool and refresh the air, and provide counterpoint to

the street noise. The plantings were designed to improve the oxygen/carbon-dioxide

balance in the air, and to provide food and home for birds, butterflies,

bats and other forms of life.

The forecourt area, while people-intensive and necessarily hard-paved, was

designed with overhead tree vegetation, moss-covered undersides of overhead

structure, ivy-covered walls, and planters in guardrails and court areas.

These were all designed to be provided water and nutrients by the same wastewater

system.

The traditional Korean garden was located in the core of the building devoted

to understanding and conveying the roots, values, and achievements of traditional

Korean culture. It was ringed by a research library, museum galleries devoted

to the traditional arts of Korea, and a performance hall for traditional

art forms. While providing a serene "breakout" space for meetings

and visitors to the center, the garden gave an intensive experience of traditional

Korean garden and architectural arts. As well, through the principle of

using community wastewater to nurture the garden's growth, and in the special

place given to the location of the garden in the arrangement of the facilities,

this garden also held a much more central role in the symbolic level of

affecting the chi of the place.

Together, these gardens helped us to share the place with other life, to

delight in the beauty, richness, and diversity of the life that makes up

a natural community, and to rediscover the sense of fit and rightness of

the natural community that had evolved in this place over the ages.

Feng-shui acknowledges that healthful surroundings and a healthful

culture must be rooted in a sacred way of living. Holding something sacred

is simply keeping the well-being of that thing inviolate. That impetus comes

only from loving deeply enough that we know the well-being of all that surrounds

us is vital to our own well being. 'Honoring' - of people, place, heritage,

the future, and our selves - is the simplest and most direct expression

of a sacred way of living, and therefore of our own survival and well-being.

The third, and perhaps most powerful level of 'chi' design involved the

minds and hearts of the users and visitors. In doing so, it dealt with

the internal arrangement, design, and symbolic meaning of elements of the

facility. In traditional Korean city and home planning, the position of

power is the north end of the central N-S axis. Here, the ruler or owner

faced and received the power and warmth from the Sun in the South, and become

the local source of power in the complex. In this project, that pattern

of arrangement was honored, and that prime location was given to tradition,

to nature, and to ancestors, in the form of a traditional garden.

Within the garden, in the position of greatest importance directly on this

axis, was placed a physically non-imposing, but symbolically vital element

- a shrine to the ancestors. This was to contain earth and icons brought

from sacred places in Korea. Its role was to give central place and honor

to the tradition, the land, and the ancestors which created the special

Korean tradition and culture, and which brought it to this place. It formed

a touchstone also for members of the community who had come from Korea or

whose family still live there, and a place to place the ashes of those with

deep ties to the "old country".

This is not of small importance. If a way can be found to show the continuing

validity and value of the principles underlying a culture and tradition

through its own design and function, the effectiveness of a museum and cultural

center dedicated to honoring, understanding, communicating and synthesizing

upon that tradition becomes an order of magnitude more successful than one

which can only preserve a discredited and dishonored tradition.

Balanced around this shrine, representing the active and passive, yang and

yin, powers of nature, were a mountain, waterfall, a traditionally-designed

garden pavilion, and a central pool of water, representing the place and

participation of people in the balance of life. From the roof, the sun-purified

waters were conducted to the mountain and waterfall, to the still waters

of the pond, and then flow outward, carrying the energy from this central

and vital place to the rest of the project and on out into the surrounding

community. Likewise, the facility honors and spreads the heritage it represents.

At the core of the facility, the garden gives a place of silence, of emptiness

- a place for things to begin, and a reflection of the primal source out

of which all creation arises.

On this same north-south axis are located the main activity spaces of the

center - a breakout space for the audience of the performance hall, opening

into the garden; the performance hall itself, with a unique stage arrangement

with openable walls allowing a variety of combinations of public and private

use; and the community forecourt which permits a more public, community

and people-oriented gathering space connected with the various parts of

the facility.

The arrangement of the 'stage' area and the performance hall was planned

to give unique opportunity for flexible and public community use, and to

restore performances to the simplicity yet effectiveness of natural lighting,

open air performance, and participatory audience arrangements. The foyer

walls slide aside, merging the performance hall thrust stage and the public

performance area in the forecourt into a single large circular stage for

large community events which can play to both the hall, the forecourt, and

the balconies around it.

Sustainability requires something be hold closely enough to our hearts that

we value it enough to devote the resources needed to its continuance. It

also requires that such maintenance be affordable. Feng-shui recognizes

the importance and wisdom of letting the renewable energies of nature wisely

channeled provide the heating, cooling and lighting of a building. All of

the elements of this KOMA design were planned to be naturally lighted, heated

and cooled, and except for the permanent exhibit areas, designed for open-air

use tied to the garden areas during the majority of the year, reducing conventional

energy needs an order of magnitude. They also were planned to use natural

and traditional building materials of the area.

The design for the facility also was based on the feng-shui principle

of durability, acknowledging that a building that lasts 200 years

costs only one-tenth of a building that lasts only 20 years. The savings

from durability permit a generosity of design that gives comfort, repose,

and fullness to its elements and its users. The expression of that goal

of durability also conveys a firm belief in the future and creates a gift

of the facility to that future, acknowledging that our own lives are built

upon the gifts of the heritage we have inherited.

This core - of permanent and temporary museum galleries, performance hall,

gardens, library, greengrocer, bookstore and newsstand - was all contained

within the traditional form of a walled enclosure - a dominant building

form not only in the Korean tradition but in many of the Latin and African

traditions which are the roots of other community residents. It was felt

a particularly appropriate form for the safekeeping of cultural treasures,

as a sanctuary from the noise, confusion, and wrongness of American urban

streets, and for security in a tension-filled community. This "enclosure"

was combined with curved roof forms which embodied the same sense of effortless,

floating support of traditional Korean roof construction in modern materials

and technologies.

The "moat" and "wall" distinguishes the facility from

surrounding areas, defines it as an honored or "sacred" area,

and makes special acknowledgment of this difference at points of public

entry. At these points, the four elements of life - earth, air, fire, and

water are given special acknowledgment or honor. A gong or a traditional

drum is located in the central entry, acknowledging the power of air, of

vibration and sound, in the organization of life from energy. Fire, in the

form of sunlight, is honored in the form of plant life it makes possible.

Earth is honored in the placement of special rocks, whose form reminds us

of our kinship with the earth, the rocks themselves, and the stars - all

ashes of earlier stars. Water is honored everywhere at entrances, for its

central role in the creation and unfolding of life.

Incorporation of traditional principles of design acknowledges their value,

and with that, the value of the culture of which they were part. Demonstrating

their effective power in new materials, technologies, climate, culture and

context not only gives greater meaning and effectiveness to the design itself,

but as well further enhances the credibility and value of the traditions

and our ability today to create with them a synthesis which opens new vistas

and dimensions of effectiveness for our current environmental design

By asking the prime question, "What can we give?", we see

what can be gained and created - free, if you wish - in the course of meeting

the program of a facility. Here both space and impetus for community place

and life were created, through careful arrangement of facilities and creation

of ancillary services that allowed community use of facilities outside the

needs of KOMA itself. We see how the impetus to neighborhood pride, fellowship,

and betterment are initiated through something as unthinkable as turning

sewage into gardens, trees, and the song of birds. We see the potency of

rediscovering the effective design principles of a tradition and finding

successful contemporary expression of them. And we see how that affects

the respect and honor we come to give that tradition, and how it affects

our own self-esteem and mutual respect. By asking the question, we are able

to create a gift of opportunity for the community - to grow, to learn, to

give, to share, and to enjoy. A community without joy is one without life.

A building, like a person, can have a soul, can affect our lives, and can

be part of the life of a community. It can be rooted in and convey the spirit

of a strong culture and tradition. It can help restore to our surroundings

a sense of sacredness and honoring of people, place, and diverse traditions.

In its organization, construction, and demands on the rest of our world,

a building can demonstrate patterns which are sustainable and nurturing

of the human spirit and of all life. Any less is not worth pursuing.

TOM BENDER

38755 Reed Rd.

Nehalem OR 97131 USA

503-368-6294

© September 1995

tbender@nehalemtel.net